As part of the first SLOT (Off-The-Shelf Online Seminar) organised by the Fédération Nanosats on 13 November 2025, Konstanze Zwintz (Innsbruck University) looked back on 14 years of science generated by observations from the BRITE constellation. With its five nanosatellites – the sixth was unable to detach from the launcher due to a lack of power at the end of the launch – this constellation, designed to perform photometric monitoring of the brightest stars, has generated more than 250 publications. Among these (to name just one) is the discovery and unprecedented temporal monitoring of Nova Carina!

A constellation optimised for the study of variable stars

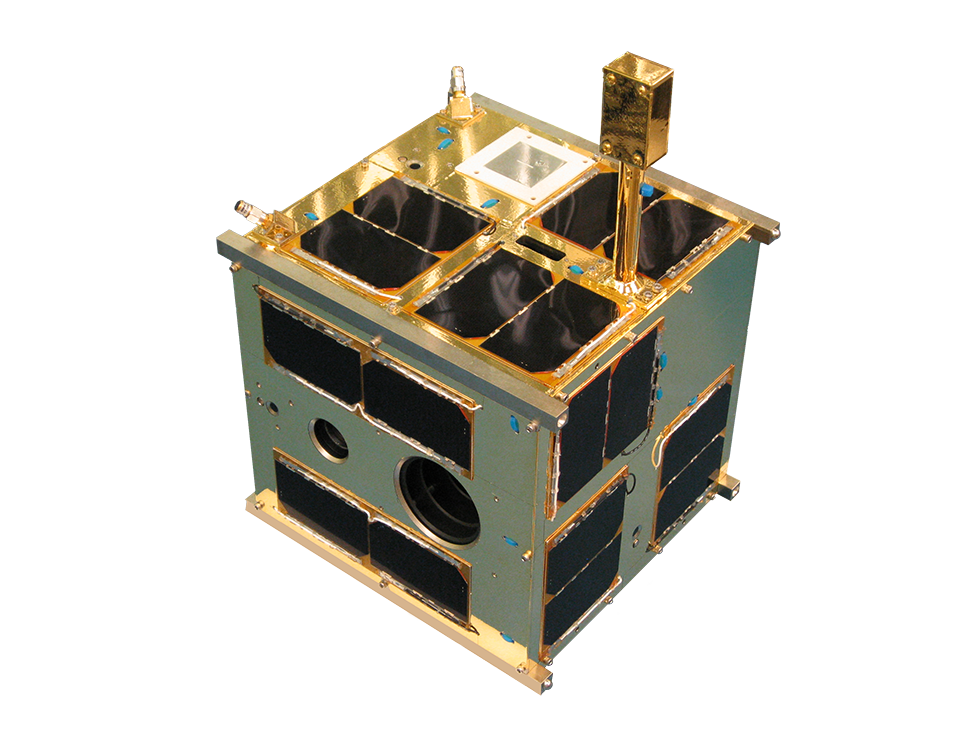

The BRITE project consists of a constellation of five nanosatellites – the sixth could not be released – launched into low polar orbits (600–900 km) between February 2013 and August 2014. It was developed by a consortium of three countries, Austria, Canada and Poland, with each national partner responsible for building a pair of nanosatellites.

Each nanosatellite, measuring 20 cm³ and weighing 7 kg, includes a payload comprising a telescope 19 cm long and 3 cm in diameter with a detector at its focal point, all stabilised on three axes. The scientific objective being to perform photometric time-series monitoring of the brightest, most massive and luminous stars, each satellite is equipped with either a blue [400-450 nm] or red [550-700 nm] filter, thus constituting a pair developed by each partner. With its wide field of view of 24 deg2, each BRITE nanosatellite is capable of observing an average of between 15 and 30 stars at the same time.

Observing from space is beneficial when studying bright stars, firstly because it allows us to escape the Earth’s atmosphere, day-night cycles and light pollution, and secondly because large telescopes on Earth are designed to detect light from faint objects and would quickly become saturated. A dedicated space project was therefore needed: the BRITE constellation.

Explore the stellar bestiary

Stars are born from giant molecular clouds, and their evolution is determined very early on by the properties of their birthplace. A star born in a low-mass environment will become a brown dwarf and live a long and dull existence for billions of years. Conversely, if a star receives a lot of mass at the outset (dozens of times the mass of the Sun), it will live a much faster and more eventful life before becoming a red supergiant and then exploding as a supernova. All that will remain of its explosion will be a neutron star or, for the most massive stars, a black hole. This stellar evolution generates variability at all stages and is therefore at the heart of the BRITE constellation deployment.

In addition, stellar configurations such as stars evolving in a binary system, others surrounded by a disc of matter, or planetary transits can also lead to variations in brightness for very different reasons which is explored by BRITE.

Last but not least, just as listening to earthquakes provides us with information about the internal structure of planet Earth, studying stellar oscillations provides us with information about the internal structure and physical processes within stars. These variations will be the primary source of variability studied with the BRITE constellation.

BRITE in 6 key highlights

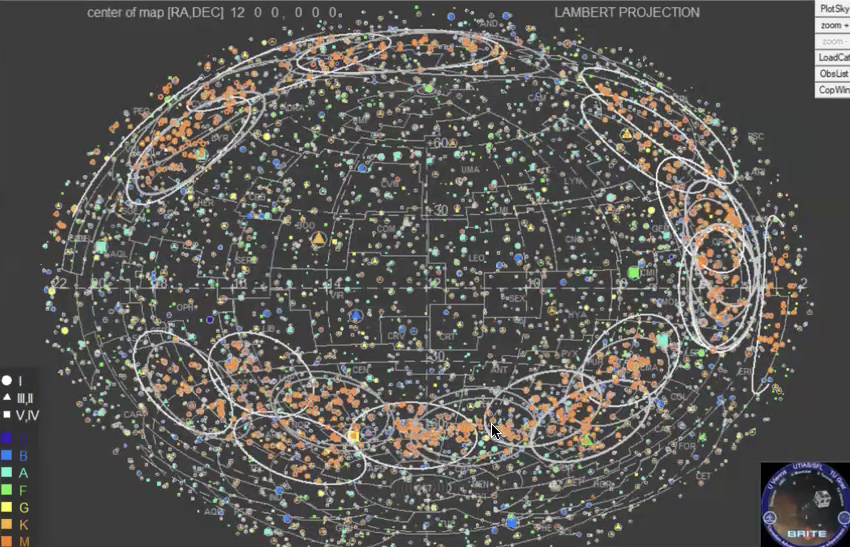

To date, the BRITE constellation has observed 753 stars in 79 fields, some of which have been visited several times. Observation campaigns of a target field have sometimes lasted up to six months, and certain selected fields have been revisited each year. The brightest star observed is Canopus (V = -0.72 mag) and the faintest is HD96265 (V = 8.03 mag).

© BRITE consortium

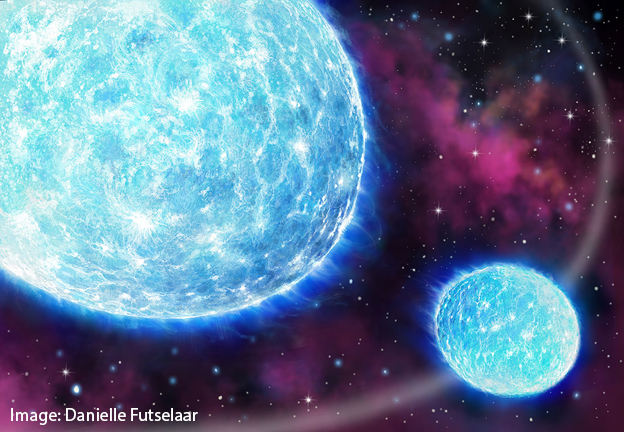

ι Orionis – the brightest star in Orion’s sword – is actually a system composed of two massive stars (~35 times the mass of the Sun) orbiting each other. With a high eccentricity (e = 0.764) and a short orbital period (29.13376 days), it was a prime candidate for observing tidal deformations when the two stars are at the closest to each other. For the first time, thanks to the BRITE constellation, a team involved in the project was able to detect a heartbeat-like variation in light on a massive star, which is a signature of this tidal phenomenon.

Pablo et. al. 2017

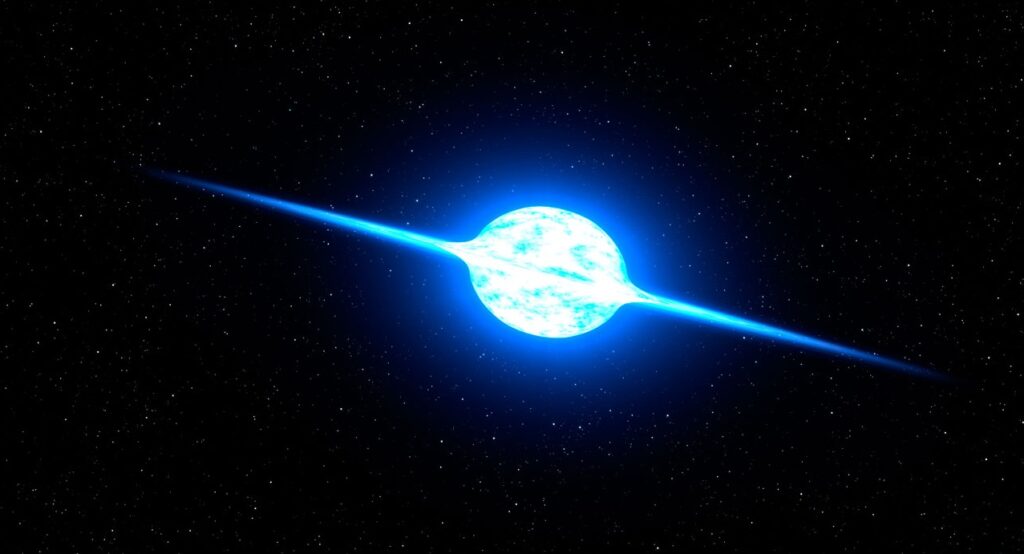

The second result concerns the study of 25 Orionis, a Be-type star, i.e. surrounded by a disc of matter. During their evolution, these stars can exhibit an excess of angular momentum, which was poorly understood until then. With the monitoring carried out by BRITE, it was concluded that the pulsations transport angular momentum, which produces ejections of matter.

Baade & Rivinius 2020

ß Pictoris is a young star relatively close to us, surrounded by an edge-on disc, whose morphology suggested that it contained at least one planet. Although planets have indeed been discovered, including ß Pictoris B in 2014 by a team involved in BRITE, a planet 10 times more massive than Jupiter, the geometric configuration of the system does not allow transits to be observed. Although predictions indicated that the Hill sphere of ß Pictoris B would pass in front of the star in 2017, it was impossible to observe it photometrically. Nevertheless, BRITE conducted a 231 days observation campaign to try to observe it, and this long time series made it possible to determine the mass and radius of the star to within ~2%!

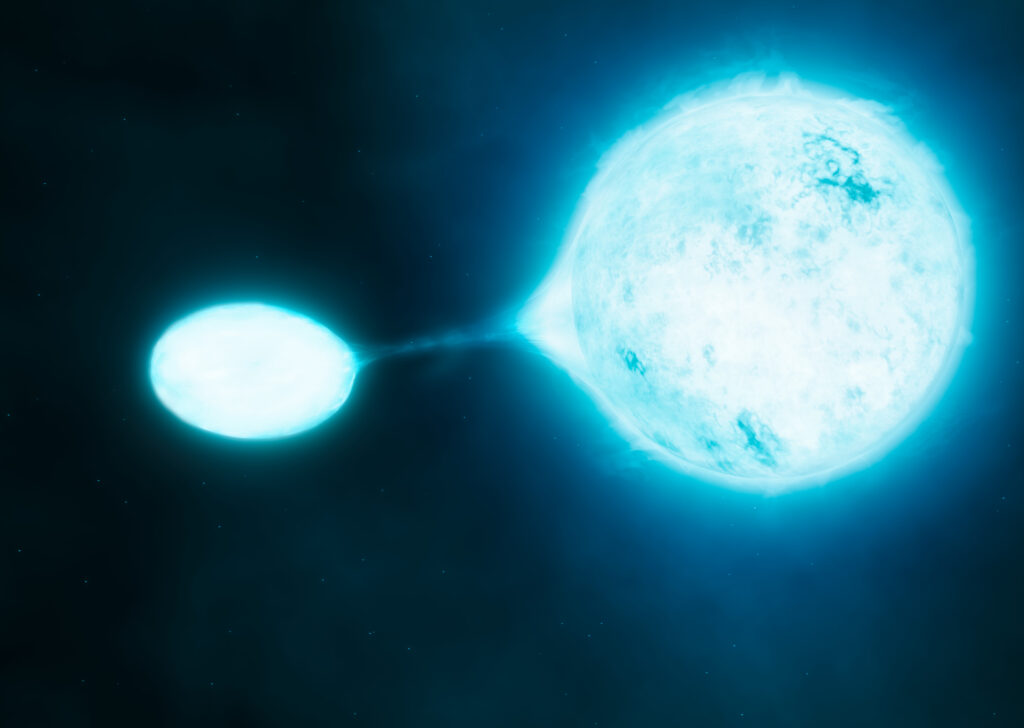

ß Lyrae is a rather special binary system in which the two stars interact and transfer mass to each other. Observations made with both filters revealed that the variations in the red are greater than those in the blue. The proposed explanation is that this could be due to an accretion disc that the less massive of the two stars might have. Although there is a long series of observations of this object, it has not been possible to confirm this hypothesis, and it will need further investigations in future missions.

Rucinski et al. 2019

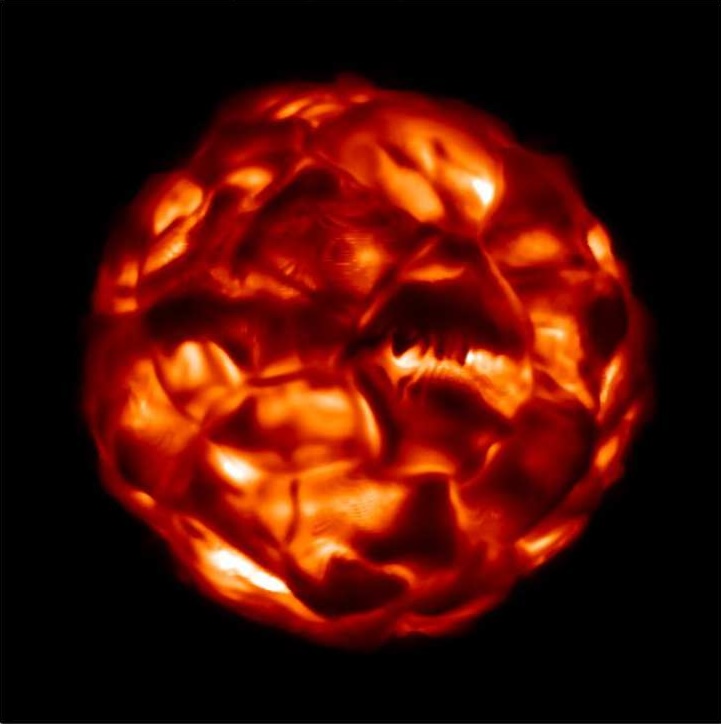

Although BRITE was not designed to do red giants asterosimology, 23 stars of this type were observed between magnitudes 1.6 and 5.3. From these photometric time series, it was possible to measure the granulation and the oscillation timescales in order to determine surface gravities and masses from stellar oscillations.

Kallinger et al. 2019

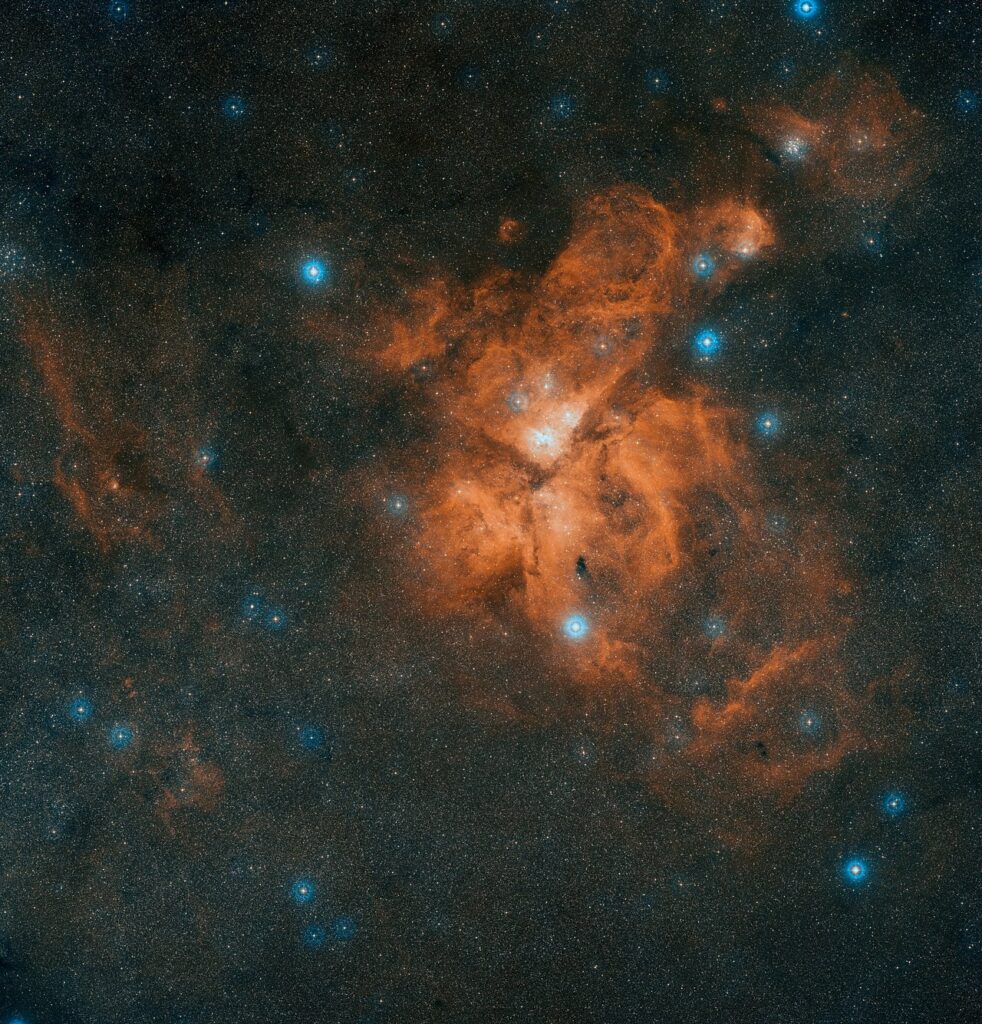

While searching for new candidates in 2018, the BRITE team selected the star HD92063 in the Carina constellation. After a few days of observations, a strange variation in light was detected in the data, which, after thorough checks, was not caused by the instruments. It turned out that a new star (V 905 Car) had appeared in the same field as the observed star. It was a nova (Nova Carina), a phenomenon caused either by a pair of red dwarfs merging or by a white star paired with another star.

Aydi et al. 2020

All publications related to the BRITE constellation can be found here.

Konstanze Zwintz is full professor Expert in asteroseismology of pre-main sequence star and chair the BRITE executive science team.